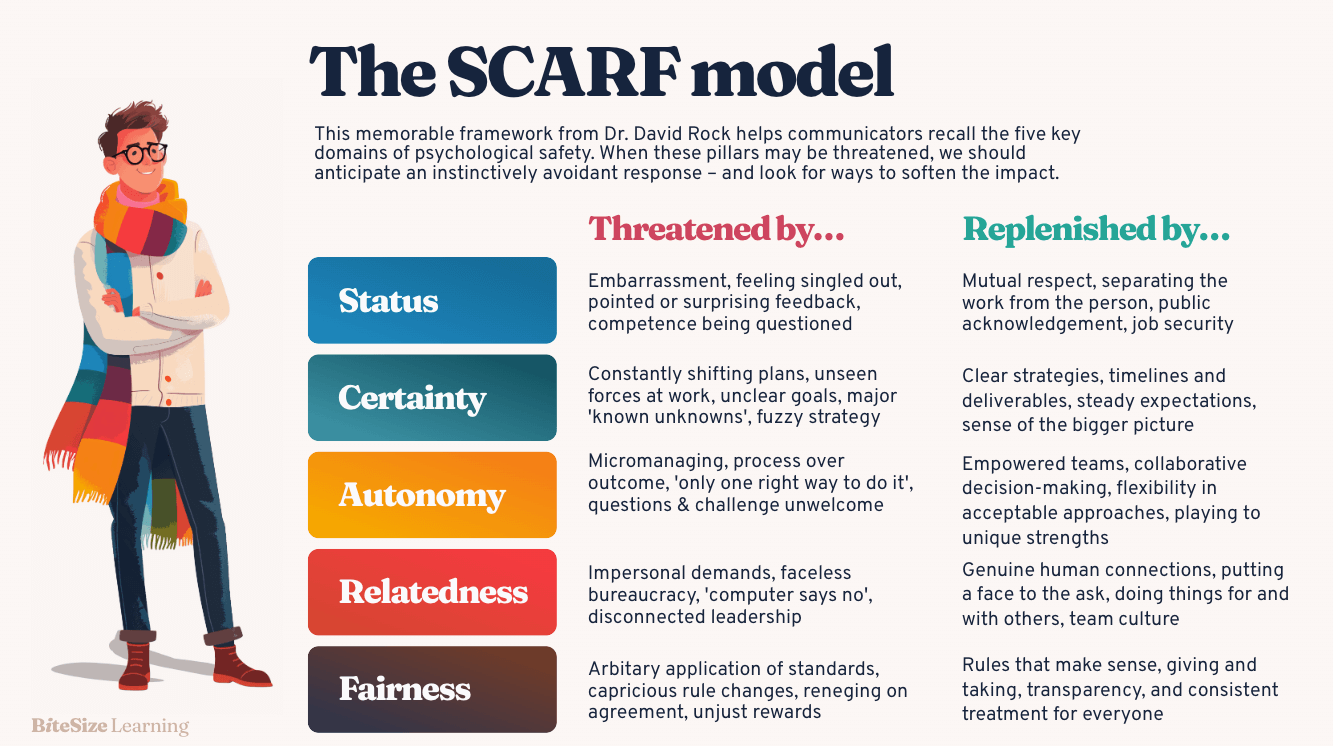

The SCARF model of social threat & reward

The SCARF model, explained

The SCARF model, introduced by Dr. David Rock in 2008, offers a straightforward psychological theory of motivation that’s easy to remember, inspired by neuroscience. Put simply, Rock argues we have strong drives to seek out five key things: status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness.

When there’s an opportunity to increase these, we often leap at the chance, finding them highly rewarding. But conversely, challenges to these five dimensions cause us to feel fundamentally threatened, withdraw, or take action to counteract the threat.

In the workplace, this explains why things like giving & receiving feedback and managing change can sometimes generate strong adverse reactions. By keeping this model in mind, we can anticipate how our actions and communications might provoke emotional responses in others, and take steps to mitigate these.

SCARF model diagram

Click here to download the graphic. Feel free to re-use it, just include a link to BiteSize Learning.

Status

Everyone wants to feel recognised, competent, accepted – even admired!

Moments that make us feel embarrassed, sheepish or overlooked threaten our need for status, and that’s why they sting so badly.

So we need to be thoughtful and deliberate when offering challenging feedback, for example. Protect the ‘status-need’ of your colleague by focusing on the work, not the person; engage with them to find shared solutions; and put extra effort into building a sense of respect and mutuality into the conversation.

Certainty

Predictability and confidence in the future are important in making us feel psychologically safe.

We tend to feel ill-at-ease when our former certainties are disrupted, trusted systems called into question or chaos reigns for too long.

If upcoming uncertainty is unavoidable, try and provide as much information as you can. Try and avoid creating additional ‘uncertainity about the uncertainty’ by bounding it with timelines – for instance, when to expect a decision – and emphasising the areas of continuity that won’t be changing.

Autonomy

Sinatra did it his way, and we want to do it in ours.

Feeling micromanaged, overruled, or controlled gets most people’s backs up.

So if you need to take control or impose changes, try to leave some room to protect the autonomy of others. (This also crops up in Daniel Pink’s theory of motivation.)

Give people some freedom to choose how things will be implemented, ask for genuine feedback, and spend extra time explaining your rationale so that they’re more likely to feel aligned with the decision.

Relatedness

We’re social creatures, and a solid connection to others can soften any defeat and sweeten any victory.

Feeling alienated from others, or operating in an unfeeling environment without the ‘human factor’, is a strong de-motivator. We need more than metrics and dashboards to feel at our best.

This is why it’s so important to nurture effective teams and build trust and rapport to create an inclusive work environment that meets our deep-seated need for relatedness.

Fairness

Difficult decisions can be accepted if we feel like they’re ‘fair play.’

But we bristle at injustice. Capricious judgements, arbitary rewards, and broken agreements are quick ways to agitate even the meekest contributor.

Ideally, we should strive to avoid unfairness altogether. Where it’s perceived in one dimension, look for ways to ‘compensate’ on another. Listen honestly to what would make people feel like justice had been done. And interrogate your own process to ask yourself if you’ve done enough to ensure a fair and consistent outcome.